用途:BTC-100X根系生长动态监测系统是利用微根管(Minirhizotron,又称微根窗)技术用于非破坏性监测分析根系动态的仪器技术,它是一种非破坏性、定点直接观察和研究植物根系的方法,其优点是在不干扰细根生长过程的前提下,能连续监测单个细根从出生到死亡的变化过程,也能记录细根乃至根毛和菌根的生长、生产和物候等特征,是估计生态系统地下C分配和N平衡研究的有效方法,结合所提供根系分析软件,能够将根系相关数据定量化,包括根的长度、面积、根尖数量、直径分布格局、死亡根及存活根数量等等。还可以根据用户需求监测土壤水分状况,从而研究根系所在区域内溶质运移及水分胁迫所引起的生理变化,广泛运用于苗木培养、作物生长模型研究、根系病理分析、昆虫行为生态等领域。

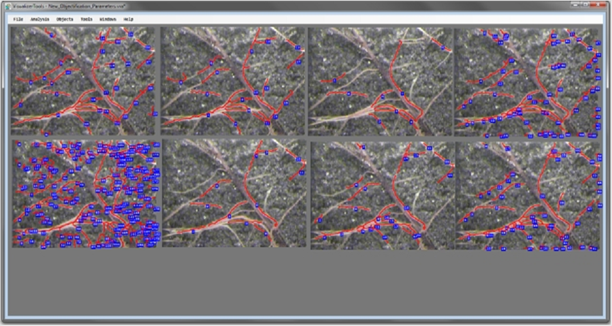

工作原理:BTC-100X根系生长动态监测系统利用微根管技术,整套系统由成像头、控制模块、手柄、光源、微根管等部件组成。将成像头伸入埋设在根系周围的微根管内,通过控制模块进行根系图像抓取成像,然后使用预装在电脑上的专业根系分析软件系统对混合图像进行分析,从而跟踪了解其生长过程。

基本组成 控制模块

手柄 带光源的成像头

分析软件

技术参数:

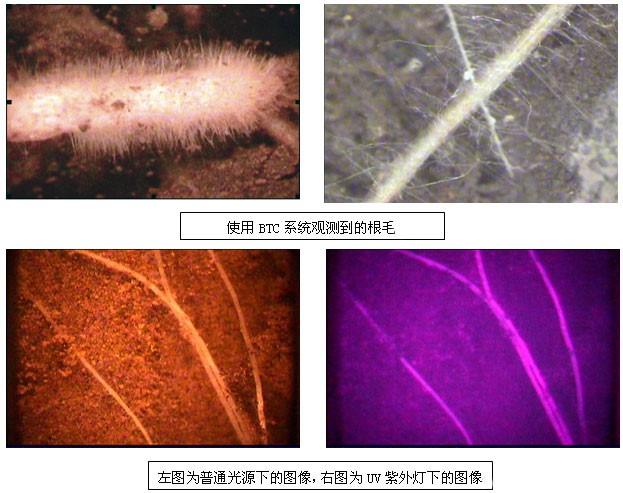

监测分析参数 | 细根长、细根直径、细根面积、细根总长、细根总面积、细根平均直径、细根数量及生物量、细根寿命、细根周转率等,其100倍高倍放大功能,可用于监测分析根毛及菌根生理生态和动态。 |

成像头 | NTSC制式彩色成像头(可选PAL制式),防水性能设计,高分辨率,带白光光源。每个视频帧看到管壁的面积为长12.5毫米×宽18毫米。 |

放大功能 | 100倍 |

光源 | 标准白光光源,可选紫外光源,以帮助识别活的细根或新萌发的根,或对荧光标记进行识别成像。 |

控制模块功能 | 控制系统含电源开关,控制成像头的光学放大缩小开关,紫外光源的开关,成像焦距的微调开关。 |

手柄 | 1.2~2.2米伸缩式手柄 |

供电 | 12V可充电电池,可连续工作约8小时。 |

连接电缆长度 | 4.8米 |

微根管尺寸 | 直径51毫米×长度1.8米,可定制其他长度观测管。 |

应用文献:

1. 白文明、程维信、李凌浩,微根窗技术及其在植物根系研究中的应用。生态学报,2005,25(11):3076-3081.

2. 李俊英、王孟本、史建伟,应用微根管法测定细根指标方法评述。生态学杂志,2007,26(11):1842-1848.

3. 邱俊、谷加存、姜红英等,樟子松人工林细根寿命估计及影响因子研究。植物生态学报,2010,34(9):1066-1074.

4. 宋森、谷加存、全先奎等,水曲柳和兴安落叶松人工林细根分解研究。植物生态学报,2008,32(6):1227-1237.

5. 于水强、王政权、史建伟等,氮肥对水曲柳和落叶松细根寿命的影响。应用生态学报,2009,20(10):2332-2338.

6. A.L.Kalyn, K.C.J.Van Rees. Contribution of fine roots to ecosystem biomass and net primary production in black spruce, aspen, and jack pine forests in Saskatchewan. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2006, 140:236-243.

7. C. E. Wells, D. M. Glenn, and D. M. Eissenstat. Soil insects alter fine root demography in peach(prunus persica). Plant, Cell and Environment, 2002, 25: 431-439.

8. Carolyn S. Wilcox, Joseph W. Ferguson, George C.J. Fernandez, etc. Fine root growth dynamics of four Mojave Desert shrubs as related to soil moisture and microsite. Journal of Arid Environments, 2004, 56:129-148.

9. Christel C.Kern, Alexander L. Friend, Jane M.Johnson, etc. Fine root dynamics in a developing Populus deltoides plantation. Tree Physiology, 2004, 24:651-660.

10. Colleen M. Iversen, Joanne Ledford and Richard J. Norby. CO2 enrichment increases carbon and nitrogen input from fine roots in a deciduous forest. New Phytologist, 2008, 179: 837-847.

11. D.G.Milchunas, J.A.Morgan, A.R.Mosiers, etc. Root dynamics and demography in shortgrass steppe under elevated CO2, and comments on minirhizotron methodology. Glogal Change Biology, 2005, 11:1837-1855.

12. James F.Cahill Jr., Gordon G. McNickle, Joshua J.Haag, etc. Plant Integrate Information about Nutrients and Neighbors. Science, 2010, 328: 1657.

13. Jinmin Fu and Peter H. Dernoeden. Creeping Bentgrass Putting Green Turf Responses to Two Summer Irrigation Practices: Rooting and Soil Temperature. Crop Scinece, 2009, Vol. 49: 1063-1070.

14. John S. King, Timothy J. Albaugh, H. Lee Allen, etc. Below-ground carbon input to soil is controlled by nutrient availability and fine root dynamics in loblolly pine. New Phytologist, 2002, 154: 389-398.

15. Laurent Misson, Alexander Gershenson, Jianwu Tang, etc. Influences of canopy photosynthesis and summer rain pulses on root dynamics and soil respiration in a young ponderosa pine forest. Tree Physilogy, 2006, 26:833-844.

16. Michael F. Allen. Mycorrhizal Fungi: Highways for Water and Nutrients in Arid Soils. Vadose Zone Journal, 2007, 6(2): 291-297

17. Seth G. Pritchard, Hugo H. Rogers, Micheal A Davis etc. The influence of elevated atmospheric CO2 on fine root dynamics in an intact temperate forest. Global Change Biology, 2001, 7: 829-837.

18. Weixin Cheng, David C.Coleman and James E.Box Jr. Measuring root turnover using the minirhizotron technique. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 1991, 34:261-267.